Mark Wright has had the opportunity to tell some very important stories throughout his career in journalism and media.

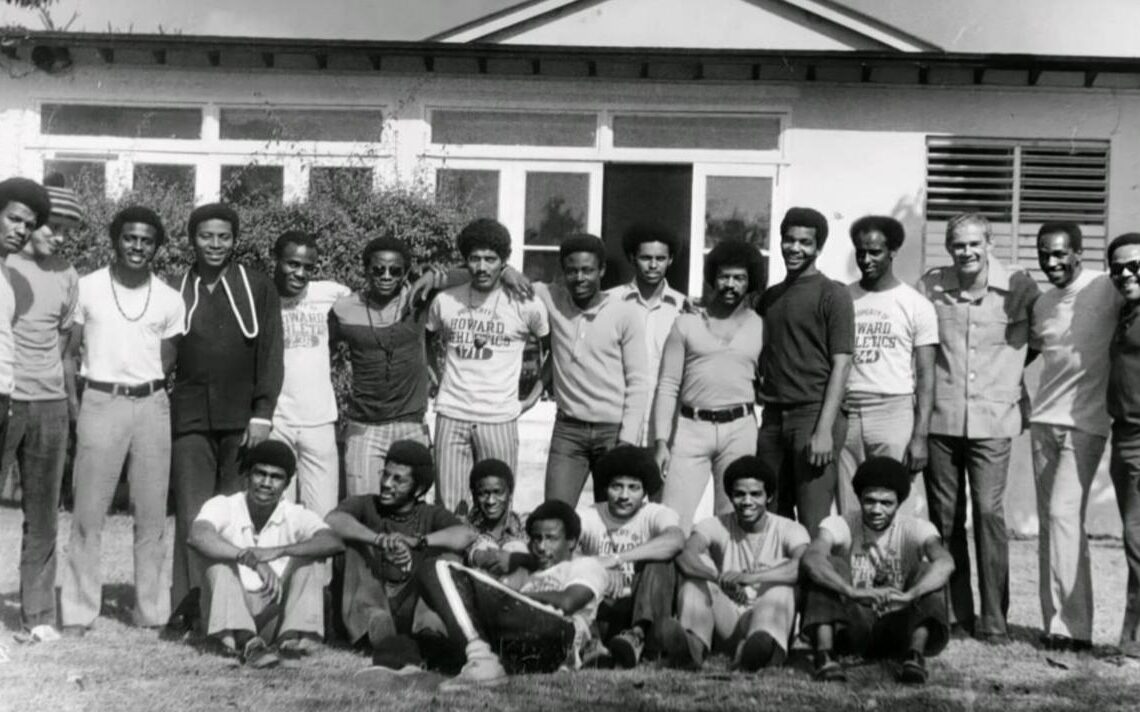

None is closer to his heart and more important than the saga of the 1971 Howard University men’s soccer team, the first HBCU to win a national soccer championship.

The controversy that surrounded the team at the time — which led to their title being stripped — is still a sore spot for all involved.

Starting Nov. 8 on Wondery Plus, the 1971 team and some of their classmates will get to tell the story as “The Bison Project,” a three-part podcast series produced by Meadowlark Media and Campside Media with Wright Creative Productions, will debut.

After its Wondery Plus debut, “The Bison Project” will be available on all podcast platforms during the weeks of Nov. 15, Nov. 22, and Nov. 29.

“It was critical for them to have their moment to tell their story,” Wright said. “These were tough interviews to do because there was a lot of joy, a lot of pain, and a lot of anger. I’ve interviewed a lot of people over the course of my career, and that’s a day I’ll never forget.”

Justice for Howard players remains elusive

The Bison defeated Saint Louis University 3-2 in the 1971 NCAA Division I championship game to cap a 15-0 season under head coach Lincoln “Tiger” Phillips.

However, player eligibility concerns motivated the NCAA to strip Howard of their championship and made it tougher for them to win in 1972, which Phillips noted in a searing speech at the Final Four banquet that year.

The 1974 team eventually broke through again for a national title and was the subject of a Wright-produced ESPN Films documentary called “Redemption Song.”

“The Bison Project,” a part of Meadowlark Media and Campside Media’s multi-platform “Sports Explains the World” series, focuses solely on the 1971 team, who finally have a chance to share their side of the story. It’s a story that Wright promises will be a revelatory and informative experience.

“The story that’s been told is the 1974 team got their just due and got their trophy, but only three players from the 1971 team played in 1974,” Wright said. “So those players still haven’t gotten their justice.”

Taking ownership of Black history

Several key members of that 1971 team, Lena Williams, the then-Hilltop student newspaper sports editor at the time, and others will talk about the rise of the team and the pain associated with being stripped of their championship without a complete explanation.

“Without being hyperbolic, this is the most important story of my career because it’s my alma mater,” Wright said. “Howard University is the place that is a big part of the person that I’ve become as a journalist and as a human being.”

“When these legends talk about their experiences in the late 60s and early 70s, the campus hasn’t changed,” he continues. “The Dust Bowl is still there; it’s a turf field now. The campus still looks and feels the same. Racism hasn’t changed either; the temperature and climate remain the same.”

The familial nature of The Bison Project is what carried Wright through a decade’s worth of hard work and determination to bring this story to light.

“I’ve gotten close to all of the players who are alive, and they all trust me to tell the story,” he says. “Ian Bain, who was a freshman in ’71 and a star on the ’74 team, was my high school soccer coach. He is one of the most important people in my life. I want to get this right for him.”

Wright has also created a Bison Project website that will complement the podcast, which is three episodes long and 102 minutes in total. He also hopes that the journey of creating The Bison Project will inspire future journalists and storytellers to take chances and find similar experiences to share.

“I worked a lot of my career at ESPN, and my focus was HBCU and HBCU stories. HBCUs only seem to matter during Black History Month or (when) a high-profile football coach goes to Jackson State,” he said. “We have more than enough stories to populate platforms outside of the month of February.”

His message is clear to HBCU stakeholders: Take ownership of the history that is out there.

“If you’re a journalist or a storyteller coming from an HBCU, you need to be offended that your stories aren’t being told,” he says. “And you need to go find them and tell them. There was a time when you needed suits to say yes. Today, platforms exist, many of which are free, where you don’t need that. Your job is to go out there and tell these stories.”